Inside the Wild, Terrifying, Bizarre, Absurd, Posthumous, Self-Funded Horror Movie That Boggled My Mind

How 15 years, vast sums of oil money, and the childhood nightmares of a meth-smoking millionaire resulted in The Evil Within.

In 2002, Andrew Getty wrote a screenplay. It was an odd little horror story, one based on recurring nightmares he’d had as a child. In the script, a developmentally disabled man is haunted by violent dreams.

In 2017, two years after Getty died of complications stemming from methamphetamine use, that movie was quietly released to streaming services under the unassuming title The Evil Within.

Everything in between is a tale almost as strange as the movie that resulted.

I stumbled on The Evil Within during a late-night scroll through the streaming services. The trailer struck me as bizarre and disturbing and intriguing in a creepy, low-budget way. And the director’s name caught my attention: Andrew Getty. Like those Gettys?

I wanted to learn more. First, I watched the movie. That was an experience. Then I looked into the backstory. Man, another experience—one I can’t help but share.

There’s a lot to cover here, so let’s start at the top—Oklahoma mineral rights in the early 20th century.

That might sound like a joke but it’s not. You see, Andrew Getty was the grandson of J. Paul Getty, once considered the “richest man in the world,” who made his fortune in oil. That fortune began with J. Paul’s father George Getty, who secured the mineral rights to 1,100 acres of oil-rich land in Oklahoma in 1903, which grew into a dynasty with billions to its name.

Those billions are the reason that J. Paul’s grandson Andrew, when he wrote his strange little screenplay, had the resources to actually turn it into a movie—unlike the screenplays of most 35-year-old dudes, which end their lives as long-neglected Final Draft files on forgotten servers. (If any millionaires wants to fund The Lost Adventures of Archie P. and Possum Pete, please let me know.)

Getty, who had written other unproduced screenplays, had an intensely personal connection to this one.

“When he was young [Getty] would have these really powerful, sick, twisted dreams,” said Ryan Readenour, a post-production producer on the film in an interview with People, “and [they were] so shocking to him that he didn’t think they came from him. … He had this idea it was this ‘storyteller’ who was creating these crazy dreams of his.”

Getty called his screenplay The Storyteller, and according to Readenour’s interview with People, he invested nearly $6 million dollars of his own money into filming it.

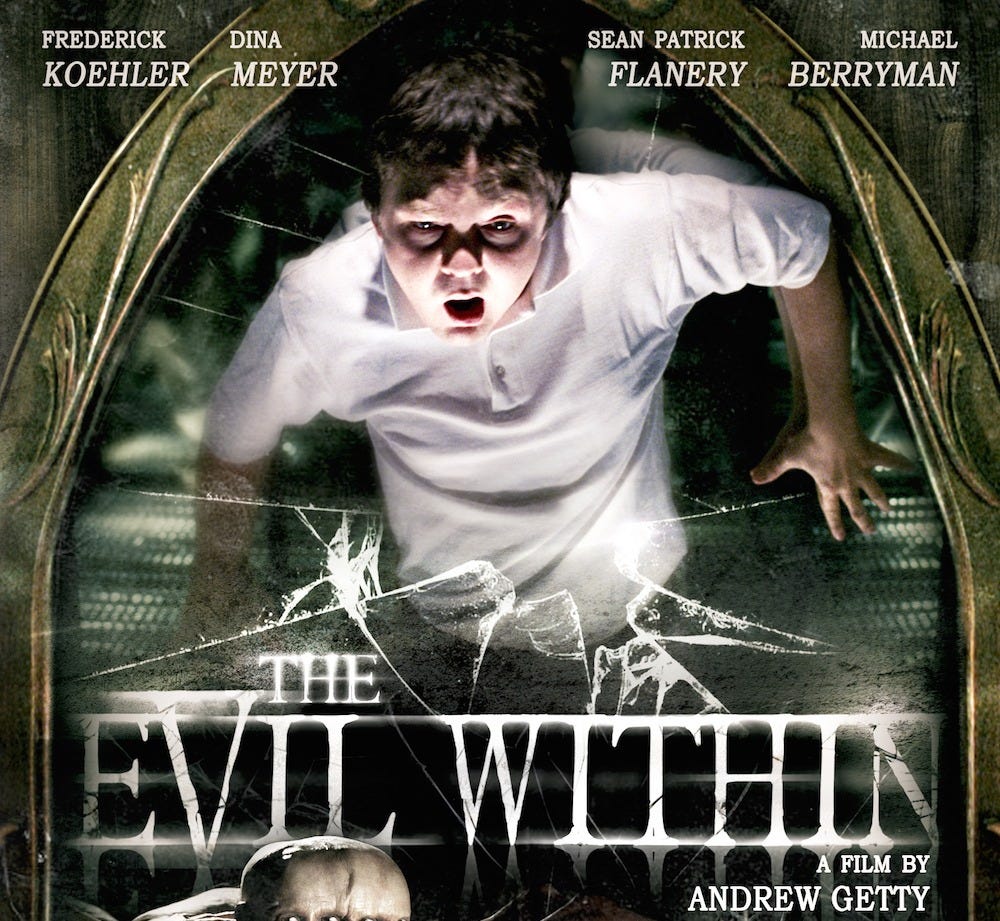

That money netted him some legit horror movie actors. There’s Michael Berryman, best known for The Hills Have Eyes, along with two future Saw franchise alums Dina Meyer (of Starship Troopers) and Sean Patrick Flannery (also known for The Boondocks Saints).

But most of that budget wasn’t about securing talent—it was about the sets and the effects that would bring Getty’s terrifying nightmares to life. He filmed most of the movie in his Los Angeles mansion, but he built elaborate and expensive original sets, including grotesque puppets and animatronics. (Not to spoil anything, but an octopus plays the drums. Also there are spider people.)

As you might imagine for a self-funded film made completely outside any studio system or traditional structure, guided solely by one millionaire’s idea, production was a bit of a mess. It went in stops and starts, with frequent delays and funding issues as Getty spent more and more of his money. In 2003, according to The Daily Mail, a studio assistant sued Getty for unpaid wages, and the resulting case aired out accusations about Getty’s behavior in court.

The Daily Mail reported, after Getty’s death: “The court heard how Getty snorted cocaine, spent heavily on prostitutes and carried a gun. … The movie’s assistant director, said she saw Getty snorting drugs while on the set. She described him as ‘a spoilt rich kid who doesn’t value his own life or that of anyone else’.”

Getty was also reportedly a heavy meth user, which eventually led to the hemorrhaging ulcer that killed him. According to NBC News, his girlfriend told police after his death that he “used an ‘8-ball’ of meth per day.”

With all that going on, the turbulent production lasted six years, finally wrapping in 2008. (For a little context from the pros, Sean Baker shot Oscar-winner Anora in 37 days for $6 million.)

But just because Getty was finally done filming did not mean The Storyteller was complete. Far from it. He converted a room in his mansion into a post-production suite where he attempted to develop his own special effects to improve the footage he had. The mounting expenses left him unable to complete the film to his standards, despite his family’s wealth.

“I remember him saying his dad is very conservative,” Readenour told People. “I don’t think they would give him the money to wrap.”

When Getty was found dead in his mansion in 2015, the film was still not finished. Michael Luceri, a producer on it, told The Hollywood Reporter that the footage just needed to be colored and edited. He decided to finish the job so that over a decade of effort and millions of dollars wouldn’t go to waste.

And so, two years after Getty’s death and 15 years after he wrote the screenplay, The Storyteller, now retitled The Evil Within, was finally released straight to video on demand in 2017.

So you might be wondering after all this, what is this movie actually like?

Real weird.

It follows Dennis, a developmentally disabled man, whose increasingly violent nightmares are haunted by a gray-skinned, monstrous man played by the aforementioned Michael Berryman. When his brother, who lives with him, brings an ornate mirror into his room, Dennis begins seeing a doppelganger of himself in the glass who tells him that if he kills things—first animals and eventually people—the dreams will stop and he’ll become “smart.”

“Essentially, I’m playing Andrew,” Fred Koehler, who played Dennis, told The Hollywood Reporter. “When [Getty] talked about the construction of the script, he would often say that a lot of the content came from his own personal dreams. He was battling with a lot of demons.”

First off, there are obvious problems with the movie. The Guardian straightforwardly sums up much of the conventional (often glaring) flaws of The Evil Within:

“Make no mistake, The Evil Within is very clearly the handiwork of a rank amateur under the influence of powerful narcotics. The film was horrifically ill-advised from the very start, working from the premise of a man with learning difficulties who commits grisly murders on the commands of his reflection in an evil mirror. Characters appear and vanish without warning or explanation, long surrealist interludes go nowhere, and the plot constantly veers into tangents that appear to bear little relevance to the rest of the film. … Needlessly complex editing schemes betray the fact that the film was pieced together from whatever scraps of footage Getty deemed usable.”

All true. Plus, the ramshackle nature of the production is easy enough to spot. An outdoor restaurant where the characters frequently eat looks like it might just be Getty’s backyard. Some of the side characters’ acting gets real wooden. And a few lines of dialogue are just baffling. (The odd conversations sometimes makes you wonder if Getty was attempting a Lynchian surrealism that just isn’t entirely pulled off.) An early wincer happens when Dennis talks to Susan, a woman who works at an ice cream store who he “has a crush on.”

Dennis: “It’s nice to see you.”

Susan: “Of course it’s nice to see me. I’m outlandishly hot.”

But this isn’t a story about a millionaire making a bad movie. The Evil Within is a seriously flawed film, no doubt about it—but it’s not straightforwardly bad. In fact, it’s one of the most fascinatingly flawed films I’ve seen in quite a while. Because, and this is pretty important for a horror movie, it’s absolutely terrifying.

This is a dark movie. Fair warning, if you’re considering watching, it gets into some real unpleasant corners, and while Getty might not have had the best ear for dialogue, he clearly had a knack for conjuring up uniquely hellish visuals.

Somehow, in between those baffling conversations and unnecessary interludes, there is a genuinely frightening, disturbing, and singular vision on display. Most noticeably in the dream sequences that Getty drew from his own childhood. In its best moments, The Evil Within becomes a spellbinding nightmare that inspires the sickening sense that you’re trapped in the dark recesses of an incredibly troubled man’s psyche.

Take the opening scene. A surreal stop-motion sequence (also a bit Lynchian) sees a home disintegrating into a woodland that transitions bizarrely to a carnival in the middle of a barren desert, as Dennis narrates a nightmare from his childhood. We see the child version of Dennis walking with his aloof, sunglasses-wearing mother. He demands to get on the “World’s Scariest” haunted house ride.

“Are you sure you want to go?” says the attendant, Michael Berryman in a comically absurd blonde wig and mustache. “Are you sure you’re ready?”

The ride carts Dennis and his mother through a dark, curved corridor. The wind rattles, the light fades, and you wait for the inevitable eye-roll of a jumpscare—but it doesn’t come. They emerge on the other side of the tunnel back into the sunlight.

As they walk away, Dennis says, “What a rip-off. We should get out money back.”

His mother looks down at him and says, “What makes you think the ride is over?”

She takes off her sunglasses to reveal mouths where her eyes should be.

“What makes you think it’s ever going to end?”

The unsettling, hard-to-shake scares intensify as the movie continues, culminating in a final sequence that—for all its absurdity—might make you want to cover your eyes and try to think about puppies.

When those expensive animatronics appear, the otherworldly creepiness makes your skin crawl. And when Berryman arrives as the gray-skinned monstrosity who haunts Dennis’ dreams, he’s enough to inspire nightmares of your own long after the movie ends.

That clear-eyed Guardian takedown quoted above points out this strange and frightening and ultimately fascinating aspect of the film, one that shows through its abundant flaws.

“The total lack of studio supervision combined with Getty’s monomaniacal drive and technical knowhow resulted in some truly outré horror, material he simply couldn’t have gotten away with under the auspices of a larger production. … And the scares Getty dreamed up were several shades weirder than anything a legitimate financier would’ve allowed. … Getty’s approach often lacks focus, but when his scares connect, they persist for many sleepless nights afterward.”

The Evil Within—the product of an obsessive, drug-rattled millionaire answering to no one but himself—is a movie not quite like any other, for better and for worse. Give it a watch, and you could find yourself laughing in derision and then gasping in horror within the span of two minutes. (And if you’re of the squeamish persuasion, it’s probably best not to watch at all.) A lot can be said about this remarkably strange movie with its mind-boggling production, but it’s certainly a unique and unlikely creation, one now hidden in the forgotten corners of over-saturated streaming services and the digital discount bins of video-on-demand.

I hadn't heard of the movie until I read this post. After watching, I was surprised by how compelling it turned out to be. Despite a lot of the low-quality stuff, the movie delivered on the promise of being gratuitously strange and blurring the line between dreams and reality.

I would rather like to watch The Lost Adventures of Archie P. and Possum Pete, i hope the Possum Pete won't have spiky-pointy yellow/brown incisors and blood dripping sharp fangs and a 20 inch tongue sticking out in place of eyes 👻